Cows’ Milk Protein Allergy or Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease – Can We Solve the Dilemma in Infants?

Salvatore et al. Nutrients 2021; 13, 297.

Background

Cows’ milk protein allergy or (CMPA) and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) are relatively common in infants in the first year of life and present with similar symptoms such as regurgitation, vomiting, crying, fussiness, poor appetite and sleep disturbances making diagnosis often challenging. Additionally, there is a lack of accurate and handy diagnostic tests. For example, gastrointestinal manifestations of CMPA are often non–IgE mediated and a clinical response to a cows’ milk-free diet is not proof of immune system involvement. As a consequence of the diagnostic difficulty both over and under-diagnosis of CMPA or GERD may occur. This review paper outlines a practical stepwise approach to help manage these infants and to help solve the clinical dilemma between GERD and CMPA.

Infant Regurgitation and Colic – Symptoms, prevalence and diagnosis

Infant regurgitation and colic affect around 20-25% of infants all over the world.1-4 In the vast majority of cases, symptoms resolve at around 4-5 months for colic and from 6 months onwards for regurgitation.5-8

Infant regurgitation is defined by the ROME IV criteria as symptoms that must include at least 2 episodes of regurgitation per day for at least three weeks in an otherwise healthy infant, 3 weeks to 12 months of age, without retching, hematemesis, aspiration, apnea, failure to thrive, feeding/swallowing difficulties or abnormal posturing.5

Infantile colic also defined by ROME IV criteria and includes recurrent or prolonged periods of crying, fussing or irritability that occur without an obvious cause, that cannot be prevented or resolved by caregivers in an infant younger than 5 months with no failure to thrive, fever or illness.5

GERD – Symptoms, prevalence and diagnosis

GERD is the more severe or complicated version of gastro-esophageal reflux (GER), it is associated with persistent, severe symptoms or complications such as respiratory problems or esophagitis. Because the definition is subjective, the terms are often misused.9 Regurgitation is the most frequently reported symptom for GER in infants but in order to diagnose GERD, an investigation-based diagnosis needs to occur. 9 Acid inhibitors should not be started unless a proper diagnosis is conducted as treatment with acid inhibitors may increase the likelihood of allergy later in life.10,11

CMPA – Symptoms, prevalence and diagnosis

The prevalence of hospital based diagnosed CMPA in the first year of life ranges from 0.5% – 3% of infants with the lowest rate when breastfeeding and food challenges are considered.12-15

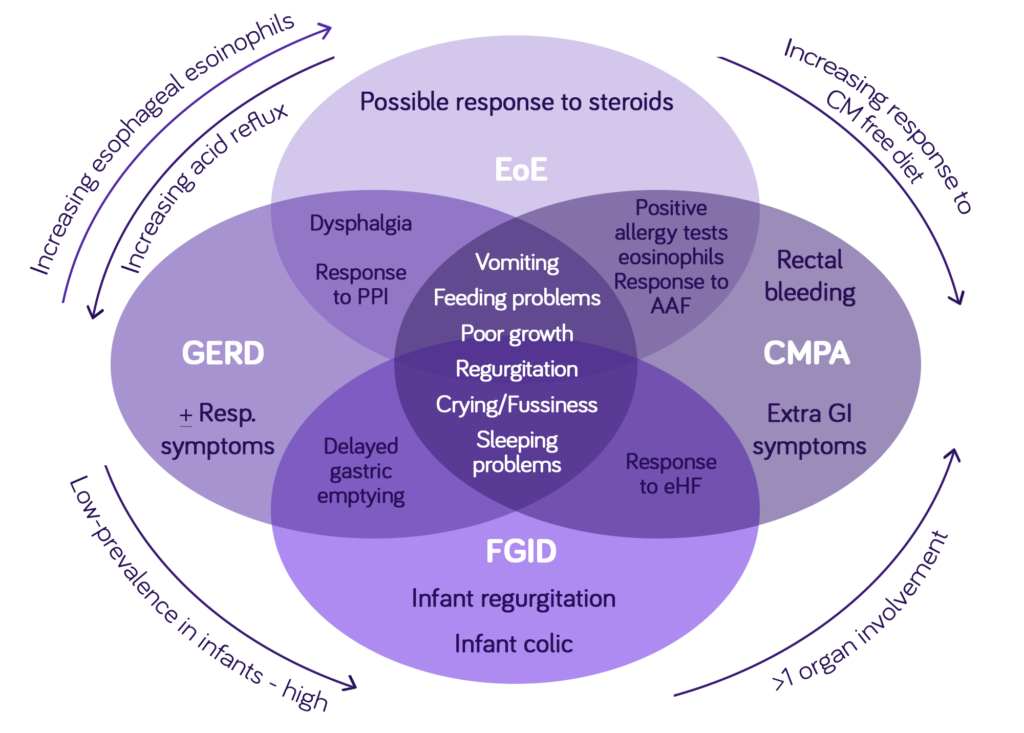

Common symptoms of CMPA include vomiting, feeding problems, poor growth, regurgitation, crying, fussiness and sleeping problems, these symptoms are similar to GERD, Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDs) and Eosinophilic esophagitis (EOE). Symptoms more specific to CMPA include rectal bleeding, positive allergy tests, response to a cows’ milk-free diet and extra gastrointestinal symptoms. (Figure 1)

The National institute for health and care excellence (NICE) GER guidelines suggest a greater likelihood of CMPA in the presence of regurgitation associated with chronic diarrhea or blood in the stool, other atopic manifestations (eczema) or a positive family history of allergy. In the ESPGHAN guidelines9,16 the involvement of symptoms in different organ systems in association with regurgitation increases the likelihood of CMPA. Both regurgitation and atopic dermatitis are common disorders in the first months of life and their relation (overlapping age, coincidence or comorbidity) still needs to be further clarified, especially in infants with severe eczema.

When diagnosing CMPA, skin prick tests and specific IgE dosage are positive in only a minority of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms.13,17 Atopy patch tests and the dosage of specific IgG antibodies are not well standardised and thus not recommended for diagnosing CMPA16,18-20 and therefore elimination of cows’ milk proteins for 2-4 weeks is the recommended approach.9,16 The oral challenge test is required for diagnostic confirmation of CMPA, proving a reaction to cows’ milk proteins after a clinical response to the exclusion.14,19-21 Given tolerance often develops in the first year of life, particularly in infants with non–IgE allergy,15 diet re-evaluation and reintroduction of cows’ milk proteins should be considered and scheduled in order to not prolong unnecessary dietary restrictions.

Gastrointestinal manifestations of CMPA are often non-IgE mediated and there is a lack of correct diagnostic classification making this difficult to diagnose.

Regurgitation, Colic, CMPA and Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) the difficulties of diagnosis

Vomiting, feeding problems, poor growth, regurgitation, crying, fussiness and sleeping problems are all common symptoms of CMPA, GERD, EOE and FGIDs e.g. colic and constipation. This can present challenges to making diagnoses. (Figure 1)

GERD may be the cause of regurgitation, vomiting, feeding disorders, day and night crying.22 Similar symptoms may also be present in CMPA and make it difficult to understand which condition is responsible for the clinical picture, especially in the absence of other signs of allergy, such as atopic dermatitis or otherwise unexplained rectal bleeding in the first months of life.1,16,17,19,23,24

The overlap of Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) with CMPA not only results from the clinical picture but also from the presence of a positive family history of allergy, atopic manifestations and positive allergy tests in about 50% of EoE cases, with a response to a cows’ milk and/or other food elimination diet in 70-90% of patients.25 The similarity of EoE to GERD is mainly based on the possible reduction of symptoms, acid exposure, and esophageal inflammation with proton pump inhibitors (PPI).26 CMPA, GERD and EoE can all occur with acute, chronic and relapsing manifestations which are difficult to differentiate between the three conditions, particularly in infants and young children.27-29,30

Figure 1: The challenging clinical overlap among Functional Gastrointestinal Disorder (FGID), GERD, CMPA and (EoE) in infants adapted from Nielsen RG et al. J Clin. Pathol. 2006;59:89-94.,27,

Conclusion

Frequent regurgitation, vomiting, distress and crying are common symptoms in infants in the first year of life. They cause distress for the baby and can be related to CMPA, GERD, FGID (including infant colic and regurgitation) and/or EoE. The difficulty is in the diagnosis with a lack of accurate tests for diagnostic classification particularly for non-IgE mediated CMPA and GERD. This can mean a delayed diagnosis and/or use of unnecessary medications such as acid inhibitors or dietary restrictions. Regular follow ups are important to avoid overuse of medications and unnecessary dietary exclusions as often through natural infant development these symptoms resolve over time.

Frequently asked questions

FOR HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL USE ONLY

- Schoemaker, AA. Et al. Europrevall birt cohort. Allergy 2015, 70, 963-972

- Burks, et al. Pediatr. Allergy Immnol. 2015, 26, 316-322

- Van Der Aa. LB et al. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2011, 42, 531-539

- Abrahamse-Berkeveld M. et al. J Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e42

- Van Der Aa et al. Clin Exp Allergy 2010, 40, 795-804

- Zhang, Y et al. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86397

- Luong A et al. Otolaryngol. Clin N Am 2008, 41, 311-323

- Hurst, DS. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 44, 637-654

- Rosen R Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:516-554

- Yadlapati R et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018,141:79-81

- Levy EJ et al. Acta Paediatr 2020;109:1531-1538

- Swanson, KS et al. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 687-701

- Peldan P et al. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2017, 47, 975-979

- Sicherer SH et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018, 141, 41-48

- Schoemaker AA et al. Allergy 2015, 70, 963-972

- Koletzko S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012;55:221-229

- Salvatore S et al. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 972-984

- Kukkonen K et al. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 119, 192-198

- Muraro, A et al. Allergy 2014,69, 1008-1025

- Fiocchi AG et al. World Allergy Organ. J. 2016;9:35

- Luyt et al. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2014, 44, 642-672

- Rosen R et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018;66:516-554

- Meyer R et al. Allergy. 2020;75:14-32

- Hait EJ et al. Clin Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019;57:213-225

- Shamir R et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol. Nutr 2013;57:S1

- Lucendo AJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;14:13-22

- Nielsen RG et al. J Clin. Pathol. 2006;59:89-94

- Yukselen A et al. Pediatr INt 2015;58:254-258

- Papadopoulou A et al. J Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014;58:107-118

- Venter C et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:468-471

- Nielsen R et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2004;39:383-391

- Host A et al. Allergy 1990;45:587-96

- Fiocchi A et al. WAO Journal 2010;3(4):57-161

- Kemp AS et al. MJA 2008; 188(2):109–112

- Vandenplas Y et al. Arch Dis Child 2007; 92:902–908

- Vanderhoof JA et al. J Pediatr. 1997;131:741-744.

- de Boissieu D et al. J Pediatr. 1997;131:744-747

- Hill DJ et al. J Pediatr. 1999;135:118-121.

Support for you and your patients

Join now and learn about our education events, research initiatives and evidence-based resources – furthering your professional development and clinical practice.

Support for you and your patients

Support for you and your patients

Join now and learn about our education events, research initiatives and evidence-based resources – furthering your professional development and clinical practice.