Exploring the Long-Term Effects of C-Sections on Infant Health and Wellbeing

What is C-Section?

What is a C-Section?

A Caesarean section (or C-section) is a surgical birth method, during which a baby is delivered via an incision made into the mother’s uterus.1 C-sections can be planned (elective), or unplanned (emergency) if complications develop such as foetal distress or maternal health risks.1,2 In other cases, mothers may choose to deliver via c-section due to personal preference, even if there is no evident health risk of vaginal birth via the lower abdomen for mother or baby.2 The number of babies born by Caesarean section has increased in Australia in recent years,3 accounting for almost 2 in 5 births (39%) in 2022, up from 32% in 2010.4 Maternal and foetal health complications like severe pre-eclampsia, and other individual circumstances may necessitate C-section delivery.3 Access to this delivery method has improved health outcomes for many mothers and infants. However, the World Health Organization recommends caesarean delivery rates should be kept below 15%.3 Despite the increasing popularity of C-sections, this delivery method does pose some short- and long-term health risks for both mother and child.3,4

It’s essential for healthcare professionals to stay on top of the latest research around c-section delivery to help optimise your patients’ long-term health outcomes. Mothers should never be made to feel shamed or judged for their choices. They must receive the informed care and support needed to make educated, safe decisions for themselves and their baby.

This article provides evidence-based, clinically relevant information about the health risks of C-sections for infants and mothers (including a comparison against vaginal delivery), the circumstances in which a Caesarean may be considered or necessary, and the scientific strategies and care you can implement to help support mothers and babies following a C-section.

Reasons for Planned and Unplanned Caesarean Section Births

C-section births are necessary in some circumstances, including when a mother or child is navigating a specific medical condition or mental health complication.1

Studies show that, in some situations, an elective and planned C-section may be necessary to ensure the health of both mother and baby. These instances include: – Maternal factors making vaginal delivery difficult or dangerous, including having delivered by caesarean section in previous pregnancies, pelvic deformities, prior perineal trauma, HIV infection, cardiac or pulmonary disease, and delivering multiple babies at one time.1,5

Uterine or anatomical indications such as abnormal placentation, placental abruption, prior hysterotomy and aggressive cervical cancer.5

– The baby being in a breech, oblique or transverse position, and unable to be turned1

– Foetal indications making vaginal delivery dangerous for the child, including congenital anomalies, thrombocytopenia, prolapse of the umbilical cord, failed vaginal delivery and previous neonatal birth trauma.5

In such cases, a caesarean section may offer short-term benefits to both mother and child, including reducing birth trauma, preventing asphyxia and ensuring the safe delivery of the baby.5 Each patient’s circumstances and preferences will determine whether a c-section delivery is a necessary or beneficial choice if these factors are present.1

In other instances, a caesarean section may be unplanned or performed in an emergency, for example:

– If the baby’s head cannot fit through the mother’s pelvis in labour

– The labour doesn’t progress, meaning the mother’s contractions are too weak and her cervix is insufficiently dilated

– The umbilical cord prolapses

– Foetal distress

– The presence of maternal health concerns or risks, such as hypertension, which may make labour risky for mother and child.1

Benefits and Risks of Caesarean Delivery

Planned caesarean section births may offer the following benefits to mother and child: – Reducing the chances of an emergency caesarean birth (currently experienced by around 1 in 5 first-time mothers in Australia) or assisted vaginal birth (which occurs in over 10% of births, with higher rates among first-time mothers4,6

– Preventing vaginal or perineal tearing during birth6

– Lower risk of urinary incontinence, compared to with vaginal delivery6

– Reducing feelings of uncertainty surrounding birth and labour.6

C-section delivery may be a safer, lower-risk option for women with specific health complications, anxieties around birth, or preferences.6 It can also be an appropriate option for women who have experienced sexual violence or trauma, for whom a vaginal birth may be too psychologically traumatising or difficult.

However, while Caesarean sections are increasingly common in Australia and are generally considered safe, they still involve major surgery and therefore pose some level of risk to both mother and child.1

Potential short-term health complications or risks of c-section births for mothers include: – Greater blood loss during birth, as well as postoperative blood loss or clotting4

– Complications in future pregnancies4 (including needing to deliver subsequent babies via caesarean section) – Pain at the wound site during recovery. The average recovery time following a c-section is around 6 weeks. However, this varies between mothers, with 10% of women experiencing discomfort for the first few months after birth following a caesarean delivery.6

– Risk of infection (in the wound site or uterus).4 2-7% of women experience infections, which can take a few weeks to heal.6

– Scarring and adhesions. During the healing process, mothers develop internal scar tissue, which can cause pain for some and may complicate any future surgeries.6

– Serious complications. While these are uncommon in women undergoing their first caesarean section birth, and those who are fit and healthy, they’re more likely if the mother has had previous c-sections or other surgeries to her abdominal area.6 While serious complications are rare, these may include the need to have a hysterectomy, maternal death, bladder or organ injury.6

– Anaesthetic complications.6

More serious health complications can also develop post-Caesarean for some mothers, so be sure to monitor for the following signs and symptoms:

– Increasingly severe abdominal or wound pain which is not resolved with pain relief medication

– Ongoing or emerging back pain at the site of the epidural or spinal injection

– Pain or burning when urinating, or inability to urinate

– Urine leakage

– Constipation or inability to pass wind

– Excessive vaginal bleeding or foul-smelling discharge

– Coughing or shortness of breath

– Swelling or pain in the lower legs

– Infection in the wound, or inadequate healing.1

Once a mother has given birth by C-section, she experiences increased health risks with each subsequent caesarean, including: – Higher risk of placental accreta in future pregnancies, which often results in heavy blood loss, and the need for blood transfusions and/or hysterectomy6

– Higher chance of uterine rupture in her next pregnancy if she has a vaginal birth. This is uncommon, but serious in the event it does occur.6 C-section births can also pose the following health risks to the infant:

– Impaired immune system development4

– Increased risk of allergy and asthma7

– Reduced microbial diversity7

– Greater risk of late childhood obesity7

– Increased risk of experiencing breathing problems at birth, and of requiring admission to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU).1

Caesarean births are generally only recommended if specific complications are impacting the safety or ability of a mother to deliver her child vaginally.4 When providing advice or guidance, it’s important to weigh up the risks and benefits of a c-section against a vaginal birth, while accounting for each patient’s individual circumstances, preferences and personal concerns. Each expecting mother’s feelings about birth will be influenced by their culture, experiences and knowledge, health status (including concerns about damage to pelvic floor, or history of difficult vaginal births), beliefs about vaginal and caesarean births, anxieties around the birthing process (including pain, labour, control, history of physical trauma), family history with birth, and mental health status.8

Help your patients manage any anxieties or mental health challenges they’re navigating around pregnancy and birth by directing them towards professional support services and care. If a patient has previously experienced a difficult vaginal birth, be sure you understand any factors that contributed, and explain the likelihood of these same complications arising again. This can help avoid unnecessary subsequent c-section births, as most women who endure a complicated assisted vaginal birth in their first pregnancy are able to deliver vaginally without complications in their next pregnancy.9

It can be useful to discuss safe pain relief options available during childbirth for your patients to consider.8 You can also connect patients with a midwife who can provide support before, during and after birth and address any questions or concerns they may have.8

Research Findings on theEffects of C-Section on Infants Long-Term

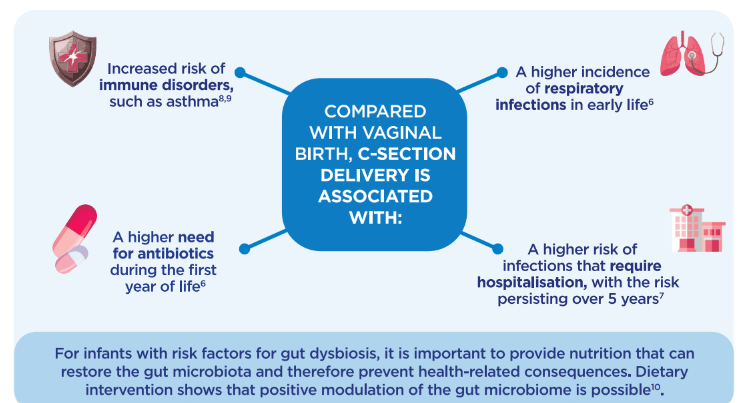

While C-sections may offer some short-term benefits to mother and child, caesarean section delivery has also been shown to have significant long-term impacts on an infant’s health and development.1-3,6,8 There is growing evidence indicating that children delivered by spontaneous vaginal births experience fewer short- and long-term health complications.3 Caesarean sections can increase a child’s risk of long-term health problems including asthma, obesity, allergies, respiratory problems and metabolic disorders.3,7

Asthma

Various studies have shown that children born by caesarean section are significantly more likely to develop asthma compared to those delivered vaginally,10,11 with other factors such as formula feeding, antibiotic use and low gestational age potentially further increasing to this risk.11

Allergies and Allergic Diseases

Infants born by caesarean section have a greater chance of developing atopic health conditions, including eczema, dermatitis, food allergies and allergic sensitisation.3,10 This may be because babies delivered vaginally inherit bacteria from the maternal vaginal microbiota during birth, allowing their early colonisation of their gut microbiota to be dominated by Lactobacillus and Prevotella.12 These immune-supporting bacterial species support the healthy maturation and function of their immune system.12

However, infants born by c-section are exposed to bacteria in the maternal skin microbiota, meaning their initial gut colonisation is often more unstable, dominated by Staphylococcus bacterial strains – many of which are pathogenic.12 This can interfere with the healthy colonisation of an infant’s gut, and compromise immune function in their early days and weeks of life.12

Metabolic Disorders

A Caesarean birth may increase an infant’s risk of developing various metabolic health conditions, with children born by emergency c-section experiencing the highest rates of metabolic disorders including type 2 diabetes and obesity by the age of 5.3 Further research is needed to confirm this link.

Obesity

Some research indicates children born by caesarean may be more likely to develop childhood obesity.13 Once again this may be linked to the differences in gut microbiota composition between infants born by C-section and vaginal birth, as well as their early feeding patterns.

While weight tends to fluctuate during early life and childhood, growing research supports the idea that childhood obesity generally continues into adulthood.13 Children who experience obesity by age 5 are more likely to have a higher body mass index (BMI), fat mass and lean mass index by the age of 50.13 Breastfed infants tend to have a gut microbiota dominated by immune-supporting bacterial strains including Lactobacillus, whereas formula-fed infants are more likely to have a more diverse, less stable microbiota.14,15 This can influence the child’s eating habits throughout their later life, impact their immune system development and function,16 and may contribute to their chances of developing childhood obesity or obesity later in life.16 Given C-section delivery has been shown to increase a mother’s likelihood to delay breastfeeding, and to stop breastfeeding sooner,17 this may further contribute to metabolic complications in infants born by caesarean section.

Respiratory Health

Infants delivered by c-section are more likely to experience breathing issues at birth, including respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), transient tachypnoea, and requiring bag-and-mask ventilation.5

They may also be more prone to developing infections in their early years, with rates of respiratory infections like pneumonia and bronchitis being higher among children born with any form of birth intervention, compared to those born without.3,18

Cognitive Performance

Some research indicates children delivered by c-section may experience slightly delayed cognitive development in their early life compared to those birthed vaginally, however the difference is minor and may be accounted for as the child ages.19

There are various factors which may explain or contribute to the differences in general health outcomes between children born via C-section (or with other interventions including induction, forceps and vacuum births), and those delivered vaginally without intervention.3

In the short term, use of forceps and vacuum during birth may cause bleeding, bruising or jaundice in the infant.20 Infants born by caesarean are also not always exposed to skin-to-skin contact with their mother, despite recommendations.21

Longer-term health discrepancies may be caused or contributed to by the following factors:

– Epigenetics: The positive stress experienced by a foetus during vaginal birth, caused by uterine contractions, infant hypoxia and other factors, has a beneficial impact on the expression of genes related to immunity and metabolic health.11 Elective C-section delivery interferes with this stress exposure, resulting in a reduced production of stress hormones in infants born by caesarean section.22 Similarly, excessive stress during birth (due to complications, induced labour or emergency c-sections) may also affect the expression of these genes, potentially causing long-term health consequences for the infant.22

– Hygiene hypothesis: Vaginal birth facilitates the transfer of gut bacteria from mother to infant, allowing the child’s gut microbiota to be colonised by health-promoting bacterial strains.3 This plays a crucial role in immune health and function, protecting the child against infection, allergy, obesity and other metabolic conditions.3 With a caesarean birth, the child doesn’t inherit the maternal vaginal microbiota in the same way, leaving them more vulnerable to health complications.3

Infant Gut Health and Immunity

As soon as an infant is born, microbial colonisation begins. A child’s initial gut microbiota lays the foundations for their lifelong healthy growth and development, influencing their susceptibility to various illnesses and health conditions in both the short- and long-term.23,24

‘Gut microbiota’ refers to the composition of microorganisms populating the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.25 The gut is the centre of the immune system, containing around 100 trillion bacteria,26 and a balanced microbiota is essential for the development of a healthy immune system.23,24 Many factors influence the colonisation of an infant’s microbiota, including gestational age, delivery (vaginal birth or caesarian section), nutrition source (breast milk and/or formula), antibiotic use during infancy, and other external environmental factors such as geographic region and the bacteria present in the hospital at birth.27-31

C-sections are one of the most significant causes of disrupted microbiota development in infants, due to the limited transmission of beneficial bacteria from mother to infant during birth.32

Vaginally-delivered infants are exposed to maternal vaginal and faecal microbes during the birth process, which then colonise their own microbiota.33 Whereas babies delivered by c-section are exposed to microbes present in the hospital and maternal skin environments, again influencing the colonisation of their microbiota.33 This can result in gut dysbiosis, which is associated with a range of short- and longer-term health complications.27-31,34

An infant’s gut microbiota plays a crucial role in early childhood development and immune function.11 Given caesarean section births delay the maturation of microbiome colonisation, this may delay development of an infant’s immune system too.11 While infants born vaginally generally have a microbiota dominated by health-promoting bacterial species including Lactobacillus, those born by c-section often have more unstable, diverse microbiota with greater quantities of pathogenic and harmful bacterial strains.7,15

This difference in microbiota composition, and the delayed maturation of an infant’s immune system have been linked to an increased risk of asthma, allergy, atopy and other health complications detailed above.7 Infants born by c-section are exposed to very different hormonal, physical, bacterial and medical factors (including antibiotics and uterotonins).7 This leaves infants more vulnerable to short-term health complications, which can have persistent impacts on the infant’s long-term health too.

Learn more about the link between C-section delivery, the infant microbiota and disease risk here.

Studies show that supplementing a formula-fed infant’s diet with pre- and probiotics can help to repair their gut and establish a more stable microbiota, containing a greater proportion of health-promoting bacteria.27-31 This is why Aptamil Gold+ contains a unique prebiotic and probiotic blend, proven to bring the gut microbiota of C section-born infants who consume formulas close to vaginally-born infants within days.*35

Based on 50 years of advanced breast milk research, Nutricia pioneers nutritional solutions to support an infant’s developing immune system and maintain good health.

*Based on total scGOS/lcFOS (9:1) and Bifidobacterium breve M-16V received by formula-fed infants as per Aptamil Gold+ Stage 1 feeding guides. Data on file.

Learn more about Aptamil infant formulas here, to help you make informed, effective recommendations to your patients when it matters most.

Infant Immune System:

The Hygiene Hypothesis The hygiene hypothesis emphasises the importance of early exposure to a variety of microbes to ensure the healthy development of an infant’s immune system.36 The theory states that children exposed to fewer microbes (due to sterile environments, lack of contact with maternal bacteria or c-section birth) may have a higher risk of developing health complications including allergies, asthma and autoimmune disease.36 While Caesarean sections are an essential, important method of delivery, they significantly impact the colonisation of a newborn’s microbiota.36 Early colonisation is influenced by various factors including the method of delivery, as well as antibiotic use before and during labour, and feeding choice (breastfeeding versus formula-feeding).36 Contact with maternal vaginal and intestinal flora allows the infant to initially develop a balanced gut microflora, supporting their immune system development.36 In a c-section delivery this contact is limited, meaning the infant’s gut becomes colonised by non-maternally derived bacterial strains. Studies indicate this may have long-term impacts on the infant’s gut health, with potential clinical implications for the immunity, metabolic health and disease risk.33,36

.

C-Section vs Vaginal Birth

There is an enduring stigma against c-sections amongst much of the medical community and the public.37 While c-sections should be prevented when unnecessary, this mode of delivery is also crucial for ensuring the health of both mother and child in various circumstances.37

When advising patients on the risks and benefits of c-section versus vaginal delivery, it’s important to understand the following factors.

Advantages of Vaginal Delivery:

– Contact with maternal vaginal and intestinal flora allows for a more balanced colonisation of the infant’s gut microflora, thereby supporting the development of their immune system.33

– Children born vaginally have a lower risk of developing atopic diseases and allergy.38

– Only vaginal delivery facilitates the production of cytokines involved in infant immunity.38

– The microbiota of vaginally-born babies has been shown to be predominantly colonised by Lactobacillus bacterial strains, while c-section-born babies are colonised by a blend of potentially pathogenic bacterial strains – which are generally found on the skin and in hospital environments.7,15,38 This can have consequences for the infant’s health and development.

– Babies born vaginally are also less likely to develop childhood asthma, especially females, and allergic rhinitis. They also have a decreased risk of experiencing coeliac disease or type 1 diabetes, among other health complications.10,11,38

– Vaginal births have been linked to shorter hospital stays after birth, lower risk of hysterectomy as a result of postpartum haemorrhage, and reduced risk of cardiac arrest compared to c-section births.7

– Caesarean section births can also delay lactation, meaning the infant’s introduction to breast milk can’t occur during their first days of life.38 Given breast milk is an important natural provider of prebiotics and other nutrients which selectively fuel the growth of beneficial bacteria strains,39 this may contribute to the disruption and dysbiosis of the gut experienced in some infants born via c-section. It can also further delay microbial colonisation and immune development.33,36,38

Benefits of Caesarean Births:

– C-sections allow for the healthy delivery of infants in circumstances where the mother or child is at higher risk or experiencing existing health concerns which complicate a natural vaginal birth.

– Caesareans also prevent or reduce the risk of certain complications associated with vaginal delivery, including vaginal tearing and injury, abdominal or perineal pain during and after birth, early postpartum haemorrhage and obstetric shock, compared against vaginal birth.36

It’s essential to use a personalised approach when making recommendations and providing care to your patients. While some people may experience some complications when giving birth vaginally following a c-section, it is often very much possible and should be discussed with each patient individually. Similarly, patients should never feel ashamed for choosing or having to deliver their baby via c-section, as this can very much be a safer and wiser choice for some mothers and children depending on their circumstances and preferences.

Providing Special Care for a Baby After a Caesarean Delivery

Babies born by caesarean are more likely to experience difficulties breathing or to require admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) – though most often they’re born healthy and without complications.1

NSW Health recommends the administration of corticosteroids when a woman enters preterm labour before 34+6 weeks’ gestation, if birth is likely within the following 7 days.40 Even a single course of corticosteroids has been shown to lower the infant’s risk of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) from 26% to 17%, as well as reducing foetal mortality and morbidity.40

In the case of a planned caesarean, the procedure is normally carried out at around 39 weeks’ gestation. If complications require the surgery to take place earlier, your patient may require steroid injections to reduce the risk of the infant experiencing respiratory problems.1,40

When an infant is born prematurely or with health complications, they may need to spend time in NICU.1 The duration of an infant’s NICU stay is highly individual and dependant on the mother and child’s circumstances, but a mother should be allowed to visit their baby as soon as they’re both well enough.1 Mothers should also receive support with expressing breastmilk or feeding their baby in the early days of their life as needed.

What to Do in the First 6-Weeks After Caesarean Birth

After a mother delivers by caesarean section, they will usually need to remain in hospital for around 2-5 days, depending on their health, recovery progress, and the hospital they’re in.1 They may also require postnatal home care from a midwife. During the first six weeks post-birth, women should:

– Prioritise rest as much as possible

– Ask for practical help and support from family and friends with things like preparing meals, cleaning and other household tasks

– Avoid lifting anything heavy

– Take slow, gentle walks daily

– Continue pelvic floor exercises to help strengthen the lower abdominal and pelvic floor muscles

– Eat a nutritious, energy-dense, high-fibre diet and stay hydrated daily.

– Apply heat to the wound to relieve pain, for example a wheat bag or hot water bottle

– Use pain relief if needed, under your guidance or recommendation

– Ensure the wound is kept clean and dry, and monitor for any indications of infection

– Wear loose, breathable clothing or high-waisted compression underwear to provide comfort and support in the early weeks after birth

– Avoid intercourse until they feel ready and have fully recovered

– Avoid driving until the wound has fully healed, and they have your approval to resume

– Join a new mothers’ group to ensure they have access to support from like-minded people navigating similar experiences and challenges. It’s important they don’t feel alone or unsupported during this time – especially during the early weeks after birth when fluctuating hormones can deeply affect mood and mental wellbeing, and the adjustment to having a new baby can feel overwhelming at times.1

Many women experience feelings of disappointment, sadness or even guilt after having a caesarean section, as there’s plenty of misinformation, shame and stigma surrounding the procedure1

– whether it’s done electively or not. Talk to your patients about how they’re feeling. Encourage them to open up to close family and friends, or to speak to a mental health professional if they need further support.

It’s important that mothers show themselves kindness and compassion in the weeks after a c-section, and prioritise their own recovery alongside the needs of their newborn baby. Recovery can take weeks or even longer – particularly if there were complications during the surgery.1

Prevention Strategies for Healthcare Professionals to Help Limit Unnecessary C-Sections

The World Health Organization’s recommendation to reduce the number of c-section births is founded on evidence showing a natural, vaginal birth is safer for both mother and child in the short- and long-term in many cases.41 Healthcare professionals can help to reduce the number of unnecessary elective c-sections by sharing the research, science and findings with patients when they’re deciding how they want to deliver their baby.41

Strategies to help reduce the number of unessential c-sections among your patients include:

– Address any risk factors or health conditions which may complicate a vaginal birth as early on in pregnancy as possible, such as gestational diabetes or breech positioning of the baby.41

– Educate and inform your patients on the benefits and risks associated with both c-section and vaginal births, so they can make more aware, considered decisions.41 If parents are struggling with anxieties around labour or birth, direct them to a mental health professional or provide resources to help alleviate their stress and anxiety, so they can approach birthing decisions with more clarity and calmness.

– The WHO also recommends continuity of care for women throughout pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period to prevent unnecessary interventions.41 It advocates for avoiding intervening earlier than necessary, recognising labour often progresses far more slowly than expected.41 Instead of continuous electronic monitoring during labour, if there are no significant risk factors then check in on the baby regularly using a hand-held monitor instead, as this again prevents unnecessary intervention in low-risk cases.41

– Consider suggesting antenatal classes and courses to your patients, such as Calm Birth, as these can assist mothers in preparing for birth and improving their antenatal education and knowledge.

By adopting an evidence-based approach to labour and birth care, you can prevent unnecessary interventions and support higher rates of natural vaginal delivery among your patients.

Will a C-Section Affect Future Pregnancies?

Having a caesarean section can impact future pregnancies. It may increase a mother’s risk of complications like placenta previa and placenta accreta spectrum disorders, severe bleeding, and needing to deliver early in subsequent pregnancies. a need for early delivery of the baby, and severe bleeding.42,43 Uterine scarring from previous C-sections can also increase a parent’s risk of uterine rupture in later pregnancies, especially in cases where a vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC) is attempted. While this is rare, uterine rupture is a serious complication requiring immediate surgical intervention.42 These risks increase with each additional c-section a mother undergoes. However, appropriate care and monitoring can help to manage these risks effectively.43 Scheduling early ultrasounds to identify the placental location, and thorough planning of the baby’s delivery can assist in mitigating these concerns.43 If a patient is considering a VBAC they should be assessed individually, and the birth should take place in a facility where emergency care is readily available in case any complications arise.43

Providing your patients with clear, evidence-based, up-to-date information and guidance can help them understand the risks of caesarean section delivery for future pregnancies. This allows patients to make informed choices about their baby’s delivery, while also accounting for their long-term health outcomes and plans.

Vaginal Birth after a Caesarean Delivery

Many parents who deliver via c-section will go on to give birth using the same method in subsequent pregnancies, making it even more vital to avoid unnecessary caesarean births where possible.5 Patients may be unable to deliver vaginally following a c-section, or choose to give birth via the same surgical method for other reasons. Once a mother has delivered by caesarean once, she’s considered to be at higher risk of obstetric complications and poorer health outcomes for herself and her baby in future pregnancies.7 Evidence shows women who deliver by c-section report feeling less satisfied with their birth experience compared to those who give birth vaginally.7 Only 12% of women in Australia opted for a VBAC (vaginal birth after caesarean) in 2022, reflecting a slight decrease from 2007.2 These low rates are largely attributed to the health risks associated with having a vaginal birth after previously delivering a baby by caesarean, with women aged 40 and over being least likely to undergo a VBAC.2,44 While it is possible to deliver vaginally in future pregnancies following a caesarean section birth, it can come with added complications and risks. This means minimising unnecessary c-section deliveries amongst your patients is crucial – particularly first-time mothers.2

Long Term Health Outlook for Mothers Post-Caesarean Birth

A mother’s recovery following a c-section birth can take several weeks to months, and they may need to stay in hospital for several days following the procedure. While we’ve discussed various potential complications that can arise during or immediately after c-section delivery, there are also longer-term factors for expecting mothers to consider: – Women are recommended to avoid falling pregnant again until their internal scar has completely healed following a c-section. This may take up to 12-18 months, with everyone’s recovery time and experience being individual. Discuss contraceptive options with your patients, particularly the mini pill if appropriate, as this doesn’t interfere with breastfeeding.45

– Breastfeeding may be impacted by c-section delivery, with studies showing women who given birth in this way are more likely to delay breastfeeding initially, and to stop breastfeeding sooner than mothers who deliver vaginally.46 Some women may experience delayed milk production, due to the physical and emotional stress they encounter during the surgical procedure and/or their decreased production of oxytocin compared to that of a vaginal birth.11,46 However, this doesn’t mean breastfeeding is unavailable – they could simply need support from a lactation consultant, and milk production may take a few days to fully initiate.46

– Mothers are often recommended to abstain from physical activity for at least 6 weeks following a c-section delivery, or until given full clearance by a qualified healthcare professional. Each woman’s recovery time and experience will be unique, so it’s important to seek support and guidance before trying anything that could compromise health or wellbeing. Generally, recovery following a c-section may take longer than it tends to after a vaginal birth.47

– Women who give birth by caesarean section have an increased risk of experiencing complications in future pregnancies, as discussed.42,43,47 These risks appear to increase with each subsequent caesarean surgery performed.

– In rare cases, women may experience chronic pelvic pain and adhesions following c-section delivery, which may impact future fertility and quality of life over the long-term.47

– Mental health outcomes should also be considered, with women undergoing unplanned or emergency caesareans having a potentially greater risk of experiencing postnatal depression or PTSD symptoms – especially in circumstances when the mother felt unprepared or unsupported during birth.47

While caesarean sections can be life-saving and necessary, they carry long-term health implications for mothers which should be evaluated when advising your patients.

Preparing Parents for a C-Section

When patients are opting for a planned c-section, the following strategies and suggestions can help them feel more physically, mentally and emotionally prepared prior to and during birth: – Provide information and set expectations early: If your patients are in the process of deciding whether to deliver via caesarean section, this is a good time to begin discussions about the reasons and practicalities of the surgery, and what the risks and benefits are for both parent and child.48 Explain all the details your patients need to be aware of in their deliberations, including considerations around anaesthesia, the recovery process, and the duration of time spent in hospital with a c-section birth. Provide them with reliable, evidence-based resources and direct them to seek further information as needed so they can make the most informed decisions possible.

– Mental and emotional preparation is key. While c-sections are a highly physical procedure, they also require a lot of mental and emotional preparation and care.48 Some patients may feel disappointed or upset if their individual circumstances mean they require a c-section birth but feel they should be delivering vaginally, with stigmas around caesareans taking a significant toll on many expecting parents.48 Others may feel stressed or worried about the physical procedure involved for a c-section, or the implications of the surgery on their own health or their baby’s.48 Encourage your patients to ask questions and express their feelings and concerns. Validate however they’re feeling and suggest strategies to help them manage their emotions – practising mindfulness, seeking prenatal counselling, attending birth preparation classes specific to c-section delivery, or speaking to a psychologist about any health-related anxieties can all be highly effective ways to help your patients feel prepared, calm and in-control prior to a c-section.48

– Physical preparation. Being physically prepared for a c-section can help your patients feel more mentally equipped for the procedure, and make the surgery itself more relaxed.48 Provide your patients with all the pre-operative instructions and guidance they need to be aware of, including details around fasting, medications, anaesthesia and hygiene considerations.48 Encourage them to pack a bag in advance for their c-section surgery, containing essential items like postpartum pads and underwear, comfortable clothing, scar care, pain relief and nourishing snacks.48 Help them arrange support at home in advance, so they’re not struggling to access midwives and other care in the early days post-surgery when they may be in pain or experiencing limited mobility.

– Post-surgery care for mother and baby. Take your patients through the post-surgery practices to ensure they and their new baby are healthy and well cared-for after leaving the hospital. Make them aware of the fact that most people need to remain in hospital for around 1-3 days post-surgery, and recovery can take several weeks or even months.48 Talk to them about plans for pain management, wound care, and how you plan to approach any potential complications that may arise.48 Discuss breastfeeding plans, and the potential impacts a c-section birth may have on their feeding preferences, ensuring you emphasise that breastfeeding is still highly achievable and beneficial even after a caesarean section birth. Reiterate the importance of early skin-to-skin contact after birth and provide referrals for postnatal care and support including lactation consultants, maternal and infant health nurses, and support groups where your patients can seek reassurance, guidance and practical help during their recovery and the early days of parenting.48

Provide your patients with empathetic, clear, evidence-based advice and strategies to help them feel prepared and empowered as they approach birth. This can alleviate anxiety and allow them to feel more confident, calm and informed, fostering a positive birth experience.

Best Practices for Healthcare Professionals: Guiding Parents Through C-Section Decisions

As a healthcare professional, you play a crucial role in supporting parents as they make decisions about the birth of their child or children. Given rates of elective c-section delivery in Australia are continuing to rise,2 it’s important to provide clear, evidence-based guidance with compassion and empathy to help your patients make more informed, educated choices.

Tailor all information to each individual patient, taking care to explain how factors like gestational age, foetal positioning and maternal health status may impact their decisions and plans for birth.

Ensure you’re encouraging open dialogue with your patients, presenting all medically viable birth options for their individual circumstances and discussing the risks and benefits of each in depth. Take your patients’ values and preferences into account and address any concerns they have with transparency and honesty.

Patients may voice concerns around the long-term health effects of a caesarean delivery on their child, including the impacts on the child’s gut microbiota, or their risk of asthma, allergies and metabolic disease. Acknowledge their concerns and provide evidence-based, up-to-date research to help your patients understand the implications of whatever decisions they make. Use plain, digestible language and avoid medical jargon, giving patients the chance to ask questions and allowing them time and space to reflect and evaluate their options before making any decisions. Involving parents in every step of the decision-making process is crucial in ensuring the best birthing experience and health outcomes for both parents and child.49 The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) advises that in the case where a c-section is suggested, healthcare professionals should clearly explain the specific reasons for this recommendation and ensure patients understand the implications and risks involved.50

Stay informed and aware of emerging research in the field and commit to ongoing learning as research and recommendations from leading organisations and bodies like the RANZCOG evolve.

Continuous professional development and learning ensure you’re providing your patients with the most current, evidence-based guidance and support possible.

By incorporating these strategies and acquiring a deep understanding of the benefits and risks of a caesarean section versus a vaginal birth in various circumstances, you can help empower your patients to make more confident, informed decisions about the birthing process, balancing their safety and long-term health outcomes with their personal values and preferences.

For healthcare professional education only.

References:

1 – Better Health Channel. Caesarean section [Internet]. Australia: Better Health Channel; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/caesarean-section

2 – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Caesarean section – National Core Maternity Indicators [Internet]. Canberra: AIHW; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/national-core-maternity-indicators/contents/labour-and-birth-indicators/caesarean-section

3 – Western Sydney University. How birth interventions affect babies’ health in the short and long term [Internet]. Sydney: Western Sydney University; 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/newscentre/news_centre/story_archive/2018/how_birth_interventions_affect_babies_health_in_the_short_and_long_term

4 – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s mothers and babies – Method of birth [Internet]. Canberra: AIHW; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies/contents/labour-and-birth/method-of-birth

5 – National Center for Biotechnology Information. Cesarean Delivery [Internet]. Bethesda: NCBI; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546707

6 – Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Considering a caesarean birth [Internet]. UK: RCOG; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/for-the-public/browse-our-patient-information/considering-a-caesarean-birth/

7 – Sandall J, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. The Lancet. 2018; 392(10155):1349-57.

8 – Davies A, et al. A qualitative exploration of women’s expectations of birth and knowledge of birth interventions following antenatal education. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2024; 24:875.

9 – Bahl R, et al. Outcome of subsequent pregnancy three years after previous operative delivery in the second stage of labour: cohort study. BMJ. 2004; 328(7435):311.

10 – Liu X, et al. Risk of Asthma and Allergies in Children Delivered by Cesarean Section: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. J Allerg and Clin Immunol: In Prac. 2024; 12(10):2764-73.

11 – Yassen AQ, et al. The role of Caesarean section in childhood asthma. J Acad Fam Physicians Malays. 2019; 14(3):10-7.

12 – Walker RW, et al. The prenatal gut microbiome: are we colonized with bacteria in utero? Pediatr Obes. 2017; 12(1):3-17.

13 – Chua WC, et al. Long-term health outcomes of children born by cesarean section: A nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. J Formosal Med Assoc. 2024; S0929-6646.

14 – Davis EC, et al. Gut microbiome and breast-feeding: Implications for early immune development. J Allerg and Clin Immunol. 2022; 150(3):523-34.

15 – Inchingolo F, et al. Difference in the Intestinal Microbiota between Breastfeed Infants and Infants Fed with Artificial Milk: A Systematic Review. Pathogens. 2024; 13(7):533.

16 – Scholtens PA, et al. Stool characteristics of infants receiving short-chain galacto-oligosaccharides and long-chain fructo-oligosaccharides: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20(37):13446–52. 17 – Hobbs AJ, et al. The impact of caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Preg and Childbirth. 2016; 16:90.

18 – Arslanoglu S, et al. Early dietary intervention with a mixture of prebiotic oligosaccharides reduces the incidence of allergic manifestations and infections during the first two years of life. J Nutr. 2008;138(6):1091–5.

19 – Blake JA, et al. The association of birth by caesarean section and cognitive outcomes in offspring: a systematic review. Social Psychiatr and Psychaitr Epidemiol. 2021; 56(4):533-45.

20 – Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Assisted birth [Internet]. UK: RANZCOG; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 8]. Available from: https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/Assisted-Birth.pdf

21 – Machold CA, et al. Women’s experiences of skin-to-skin cesarean birth compared to standard cesarean birth: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open. 2021; 9(3):E834-40.

22 – Martinez LD, et al Cesarean delivery and infant cortisol regulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020; 122:104862.

23 – Knol J, et al. Colon microflora in infants fed formula with galacto- and fructo-oligosaccharides: more like breast-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroent and Nutr. 2005; 40(1):36–42.

24 – Bruzzese E, et al. A formula containing galacto- and fructo-oligosaccharides prevents intestinal and extra-intestinal infections: an observational study. Clin Nutr. 2009; 28(2):156-61.

25 – Oozeer R, et al. Gut health: predictive biomarkers for preventive medicine and development of functional foods. British J Nutr. 2010; 103(10):1539–44.

26 – Mitsuoka T. Intestinal flora and aging. Nutr Rev. 1992; 50(12):438–46.

27 – Mitchell CM, et al. Delivery Mode Affects Stability of Early Infant Gut Microbiota. Cell Rep Med. 2020; 1(9):100156.

28 – Wopereis H, et al. The first thousand days—intestinal microbiology of early life: establishing a symbiosis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014; 25(5):428–38.

29 – Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). Immune System Disorders Fast Facts [Internet]. Australia: ASCIA; 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 11]. Available from: https://allergy.org.au/patients/immune-system/immune-system-disorders-fast-facts

30 – Akagawa S, et al. Development of the gut microbiota and dysbiosis in children. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 2021;40(1):12–8.

31 – Petersen C, et al. Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease. Cell Microbiol. 2014; 16(7):1024–33.

32 – Bogaert D, et al. Mother-to-infant microbiota transmission and infant microbiota development across multiple body sites. Cell Host Microbe. 2023; 31(3):447-60.

33 – Milani C, et al. The first microbial colonizers of the human gut: composition, activities, and health implications of the infant gut microbiota. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2017; 81(4):e00036-17.

34 – Carpay NC, et al. Microbial effects of prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics after Caesarean section or exposure to antibiotics in the first week of life: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2022; 17(11):e0277405.

35 – Chua MC, et al. Effect of Synbiotic on the Gut Microbiota of Cesarean Delivered Infants: A Randomized, Double-blind, Multicenter Study. J Paediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017; 65(1):102-6.36 – Okada H, et al. The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Experimental Immunol. 2010; 160(1):1-9.

37 – World Health Organization. Caesarean section rates continue to rise, amid growing inequalities in access [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/16-06-2021-caesarean-section-rates-continue-to-rise-amid-growing-inequalities-in-access

38 – Neu J, Rushing J. Cesarean versus vaginal delivery: long-term infant outcomes and the hygiene hypothesis. Clin Perinatol. 2011; 38(2):321–31.

39 – Moossavi S, et al. The Prebiotic and Probiotic Properties of Human Milk: Implications for Infant Immune Development and Pediatric Asthma. Front Pediatr. 2018; 6:197.

40 – NSW Health. Management of Threatened Preterm Labour [Internet]. Sydney: NSW Health; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/GL2022_006.pdf

41 – World Health Organization. WHO statement on caesarean section rates [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2015 [cited 2025 Aug 11]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/161442/WHO_RHR_15.02_eng.pdf

42 – The Royal Women’s Hospital. Caesarean birth [Internet]. Melbourne: The Royal Women’s Hospital; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.thewomens.org.au/health-information/pregnancy-and-birth/labour-birth/caesarean-birth

43 – Queensland Health. Selected adverse maternal outcomes following a previous caesarean section in Queensland [Internet]. Brisbane: Queensland Health; 2010 [cited 2025 Aug 4]. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/361731/statbite30.pdf

44 – Attanasio LB, et al. Women’s preference for vaginal birth after a first delivery by cesarean. Birth. 2019; 46(1):51-60.

45 – NSW Health. The mini pill (Progesterone Only Pill [POP]) – A contraceptive option for breastfeeding women [Internet]. Sydney: Western Sydney Local Health District; 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/factsheets/Documents/the-mini-pill.pdf

46 – Li L, et al. Breastfeeding after a cesarean section: A literature review. Midwifery. 2021; 103:103117.

47 – Orovou E, et al. Prevalence and correlates of postpartum PTSD following emergency cesarean sections: implications for perinatal mental health care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychol. 2025; 13:26.

48 – Pregnancy, Birth and Baby. Planned or elective caesarean [Internet]. Canberra: Healt

thdirect Australia; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.pregnancybirthbaby.org.au/planned-or-elective-caesarean

49 – Healthdirect Australia. Elective caesarean section [Internet]. Canberra: Healthdirect Australia; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/surgery/elective-caesarean-section