Mild Cognitive Impairment is defined as significant memory loss beyond that which would be expected due to normal ageing without the loss of other cognitive functions and refers to the transitional state between the cognitive changes of normal ageing and very early dementia.1

MCI is a common condition encountered by clinicians and is estimated to occur in 12–18% of people aged ≥60 years.2

MCI is heterogeneous but in approximately 50% of cases represents a transitional state between normal aging and dementia.3

It is estimated that people with MCI have a 3 to 5 times increased risk of developing dementia with about 15% of patients progressing to dementia each year.4

In 2001, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) set the following criteria for use by medical practitioners in determining if a person has MCI4,5

- Report of memory problems, preferably confirmed by another person.

- Measurable, greater-than-normal memory impairment detected with standard memory assessment tests.

- Normal general thinking and reasoning skills.

- Ability to perform normal daily activities.

A recent update of these criteria allows the person to be unaware of the memory problems and allows more complex activities, such as managing finances, to be affected.6

What is Mild Cognitive Impairment and how does it differ from normal aging?

MCI causes cognitive changes that are serious enough to be noticed by the person affected and by family members and friends but may not affect the individual’s ability to carry out everyday activities.2

Presented by Associate Professor Michael Woodward AM, Geriatrician & Director of Aged Care Research, Austin Health

Associate Professor Michael Woodward discusses Mild Cognitive Impairment and how it differs from normal ageing and dementia .

It can be challenging to differentiate MCI from normal ageing.

| Normal Ageing | MCI |

|---|---|

| Occasionally losing items in the house. | Misplacing/ losing items in the house keys/wallet more regularly so a fix is put in place – eg a hook at the front door. |

| Forgetting appointments or events occasionally and usually for a reason like fatigue or stress. | Having trouble keeping track of dates and appointments so now using a diary all the time/ white board in the kitchen. |

| Occasional trouble recalling the names of people or places. | Having occasional difficulty finding the right word for items usually known e.g. ‘carburettor’ for a car mechanic or ‘the bowers’ for a bridge player. |

| Going the wrong way in less familiar environments e.g. new city or large shopping centre. | Double checking the route even if travelled before. Errors in navigating to familiar places, not taking the most direct route. |

| Can tire more easily. | Unexpected irritability, anxiety, depression or apathy. |

| Takes more time to learn a new or unfamiliar process e.g. setting up a new appliance. | Struggles with more complex processes and needs assistance e.g. eBanking/credit card or smartphone updates. |

| Clinical examples provided by Associate Professor Mark Yates, Geriatrician. September 2022 | |

What is the trajectory for patients with MCI?

GPs play an essential role in the early detection and management of MCI with the possibility of stabilising and even reversing cognitive decline if treatable causes are identified and managed.

Presented by Associate Professor Mark Yates, Geriatrician, Grampians Health and Deakin University and Associate Professor Michael Woodward AM, Geriatrician & Director of Aged Care Research, Austin Health

Associate Professors Mark Yates and Michael Woodward discuss the possible trajectories for a person with Mild Cognitive Impairment.

Early and accurate diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment provides a window of opportunity to improve patient outcomes using a personalized care plan including lifestyle modifications to reduce the impact of modifiable risk factors (for example, blood pressure control and increased physical activity), cognitive training, dietary advice, and nutritional support.3

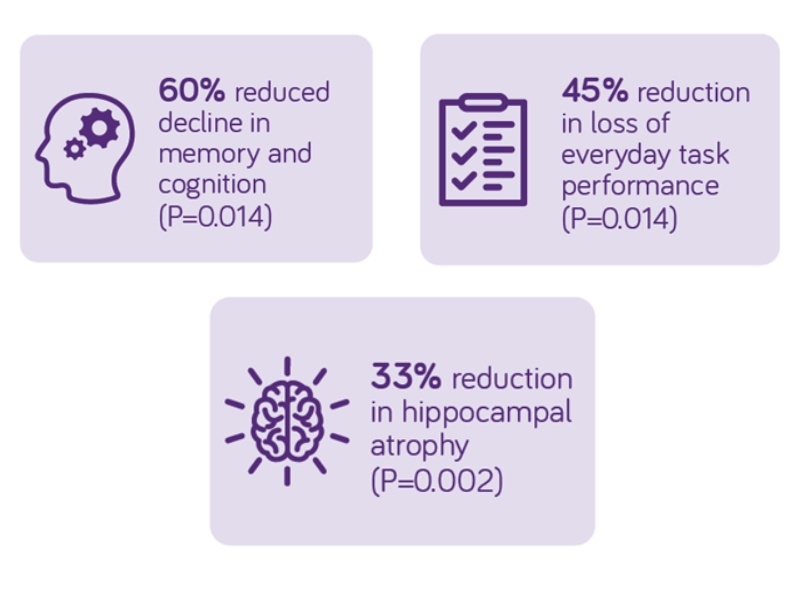

Souvenaid® slows the decline of cognition and memory by 60% in MCI (Prodromal AD) when taken daily over 3 years9

Souvenaid® is a once-daily medical drink containing a combination of nutritional precursors and cofactors (long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, uridine, choline, B vitamins, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium), and was developed to support the formation and function of neuronal membranes and synapses.10

LipiDiDiet Results

The European Commission-funded LipiDiDiet Clinical trial9 investigated the impact of Souvenaid® on patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment (prodromal AD).

The daily consumption of Souvenaid® over a 3-year period significantly slowed decline in cognitive function, thinking skills, memory and brain atrophy compared to placebo9.

The authors conclude that the present study provides evidence for potentially altered disease trajectories supporting the positive effects of long-term multi-nutrient intervention in prodromal AD.9

First Australian MCI Recommendations

Recent Australian recommendations on approaching the Detection, Assessment, and Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment have also supported the role of Souvenaid® for patients with MCI.7

Recommendation 28

“A medical food, Fortasyn® Connect*, has been shown in one 3 year randomised controlled trial to slow the decline in cognition and delay hippocampal atrophy in those with prodromal AD, and patients with MCI should be informed of these results and the availability of Fortasyn® Connect in Australia.7,9”

*Souvenaid® contains Fortasyn® Connect.

Please see below link to access the publication

Souvenaid® is a food for special medical purposes for the dietary management of early Alzheimer’s disease and must be used under medical supervision.

- Petersen, R., & Negash, S. (2008). Mild Cognitive Impairment: An Overview. CNS Spectrums, 13(1), 45-53

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement 2022;18. Available online: https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf (accessed September 2022).

- Cummings J et al., Souvenaid in the management of mild cognitive impairment: an expert consensus opinion. Alzheimer’s Res Ther. 2019 Aug 17;11(1):73

- Dementia Australia. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Available online: https://www.dementia.org.au/about-dementia-and-memory-loss/about-dementia/memory-loss/mild-cognitive-impairment (accessed September 2022).

- Petersen RC et al. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001 May 8;56(9):1133-42

- Ronald C. Petersen et al. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment. Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology Jan 2018, 90 (3) 126-135;

- Woodward M, et al. Nationally Informed Recommendations on Approaching the Detection, Assessment, and Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, vol. 89, no. 3, pp. 803-809, 2022. Nutricia has no affiliation with the authors of this publication.

- Shimada H, et al. Reversible predictors of reversion from mild cognitive impairment to normal cognition: a 4-year longitudinal study. Alzheimer’s Res Ther. 2019;11:24

- Soininen H, et al. 36-month LipiDiDiet multinutrient clinical trial in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021;17:29–40

- Sijben J et al. (2011). A multi nutrient concept to enhance synapse formation and function: Science behind a medical food for Alzheimer’s disease. OCL. 18. 267-270. 10.1051/ocl.2011.0410.

- Scheltens P et al. Efficacy of a medical food in mild Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized, controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement 2010; 6(1): 1–10.e1.

- Scheltens P et al. Efficacy of Souvenaid in mild Alzheimer’s disease: results from a randomized, controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis 2012; 31(1): 225–36.